Include+ Principles in Oral History

Care, Curation and Challenge : Aligning Mhor Collective’s work on Oral History in Castlemilk with the INCLUDE+ Principles

Using digital inclusion to celebrate and enhance community power and cohesion

Introduction

At Mhor Collective, our aim is to adopt “a human rights approach to digital inclusion”, and we emphasise that the process of including everyone in the digital sphere is inextricably linked to improving social equality. We work in partnership with stakeholders throughout Scotland as well as elsewhere in the UK and in Canada, delivering training, producing research, developing services and conducting evaluations.

This review examines the work of the Castlemilk Oral History group, from its forebears, to its inception, to the development of the work and finally its launch as a website and celebration event. Rather than coldly analysing the project in academic terms, what follows is a personal account that verges on autoethnography, interspersed with the voices of community members who were co-participants.

Background

Our work together began late in 2024, with a short programme entitled “Be The Media!” Over four weekly sessions, we looked at taking, editing and sharing photos, moving onto video, audio and the written word. Our sessions were hosted by Cassiltoun Housing Association, a long-term partner organisation for us in the Castlemilk area of Glasgow.

Key to this project was a theme of citizen control, meaning that it overlapped with questions of media literacy:

- Who chooses what’s depicted?

- How do they frame it?

- What text accompanies what image or sound?

- How does that affect the viewer?

In one session, echoing the ‘conscientisation’ methods of Paulo Freire, I used a method of visual stimulus, showing a photograph of a litter pick by Cassiltoun staff members. Participants were asked how viewers might hypothetically comment on the picture, with responses ranging from “it’s brilliant what they’re doing” and “they’re helping the community” to “they shouldn’t have to do that” and “shocking, they should concentrate on the repairs to people’s houses instead.” While it should be noted that these were not necessarily the views of the attendees themselves, this showed how an image can be differently received.

We then showed a picture of a sleeping firefighter with mock headlines, showing not only the contrast in narratives but also deconstructing the legitimacy of what may, at first sight, appear to be genuine news content.

Control was also a theme in the sense of community members being active producers, instead of passive consumers, of media. Therefore, we discussed engaging with existing media critically, while also becoming equipped with new discoveries in photography, video capture and sound recording, to tell their own stories.

Key to this session was the notion of transferable skills – the taps, swipes and other actions that lead on from media capture. So, we shared our photos, emailed our videos, found our captures on our devices and renamed them, centering these core skills within the vehicle of media creation. Under the hood, the sessions were essentially about navigation around a smart device.

The programme was well-received, with members requesting further sessions on other aspects of their devices. Through discussion with community members and Cassiltoun’s Community Team, we decided to launch an oral history group. This idea was enthusiastically developed by the group members. Hence this relatively small media literacy project, which acted as a catalyst for building both community capacity and digital empowerment, was able to grow through our co-design and participatory approaches into a larger and longer-term commitment.

In what follows, I will discuss and assess this project in light of the Include+ principles, a suite of concepts that are “meant to guide us when designing and implementing community-centred projects in ethical and inclusive ways.” While the principles are mainly aimed at assessing what sort of research Include+ will seek to support, they are also a highly effective lens for considering the strengths and purpose of digital inclusion activity more generally.

Meaningful Digital Inclusion

Of all the Include+ principles, this most directly maps onto the project. At Mhor, we’re big fans of the ‘hook’, the One Weird Trick that gets people interested in their digital device. It could be knitting, or football, or face-timing a relation, but it’s something you care about, and the swipes, clicks and taps they require are the inroads to a host of transferable skills that open up the device’s potential

I would suggest that there are two core concepts behind this principle: that digital inclusion should be relevant and that it should be resonant.

Group members were passionate about the idea of preserving and celebrating the social history of Castlemilk, particularly older folk who recognised the risk of a rich tapestry fraying in the winds of time. As a post-war housing scheme, many of the people who were born or moved there in very early childhood are now elderly; frankly, the lived experience of mass movement to the new estate, both positive and negative, isn’t going to live forever. Group members felt it was important to build an archive of this shared past.

Castlemilk is not the place it was in the late 1950s. Many of the memories we captured spoke of the lush, green, clean and aspirational place they first encountered, like Bessie’s belief that “the sun seemed to shine all the time”:

Equally, there was a feeling in the group that “history isn’t all about lords, ladies and castles. We believe everyone has a story to tell.” There’s an almost moral imperative at play here: that it’s only right for the full range of human experience to be captured and shared. While it’s certainly more common nowadays to hear of a “People’s History of…” this or that, the justification behind it is that we’re still overfed tales of the great and the good as the motors of history. The group felt this resonance keenly and were driven to build up their recording skills to address this persistent imbalance.

Collective Care

This is without doubt my favourite principle, and not just because it references mutual aid, a central pillar of my work. Collective care is about nurturing and embellishing the self-sustaining bonds within communities so that growth is jointly derived and communally shared.

In our project, again, we were all involved in gathering memories, and when new skills were in play we’d often pair up so that members would discover and develop together. While I’d facilitate these sessions and ‘float’ amongst pairs to answer any queries, it was common for participants to lead each other through the task. They’d meet socially or off-site to make recordings and help each other with intermittent queries. And maybe some of those times, they’d get stuck together, because it’s ok to feel it’s ‘not just you’ who doesn’t get it.

More generally, this project was one of collective care because the Castlemilk community was stewarding its own archiving, deciding what to record, who to speak to, and how those recordings would be heard. A shared history is a common identity.

But who counts as the collective? I was a group member and did not consider myself external to my accomplices, so amongst the archive, you’ll hear my voice as both interviewer and interviewee. In my work, there’s an important difference between ‘let’s get all those folk over there singing and dancing as a group’ and ‘let’s all sing and dance together’. So, I embraced this, learning so much about Castlemilk and its people, fully meeting Freire’s idea of the ‘teacher-student’ who gathers as much as he gives, and equally my co-participants were ‘student-teachers’ who reciprocated this balance. In one of my favourite passages, Freire goes one blissful step further than this formulation, whereby:

“at the point of encounter there are neither utter ignoramuses nor perfect sages; there are only people who are attempting, together, to learn more than they now know.”

This forms a dissolution of the ‘teacher-student/student-teacher’ dialectic, to people who are learning and sharing collectively. Group members repeated this process, as they recorded their own and each other’s recollections, as well as those of others in the community.

It’s important to state that in other ways the project ran counter to the Include+ description of collective care. Most notably, group members were not “properly remunerated for their time,” as they were not paid at all! However, this element of the principles directly relates to projects funded by Include+; not only was our oral history project unfunded by them, it wasn’t funded by anyone besides Mhor Collective contributing my time. This wasn’t quote-unquote ‘research’, it was community activism and Ivan Illich-style ‘conviviality’ in action, sharing time and skills with a view to bolstering social cohesion. As such, it doesn’t entirely fall under the remit of the Include+ rubric.

Nonetheless, there are intriguing points here. Would it have been better to pay the group members to celebrate their neighbourhood? Should I be paid when I repurpose food waste for a community meal at the weekends? Couldn’t people at climate protests or arms blockades be funded for their time? Can I only drive to the shops for my neighbour if they pay for my petrol? There are many views here, from those who highlight, in line with Include+, that remuneration is a key factor in equity, to those who rail against the notion of ‘work’ in community activism.

However, it’s unfair to critique the project on financial grounds, because it wasn’t a pure research initiative. There’s often a muddy line between when we stop doing community ‘work’ and when we’re living and acting as community members. Knowing many of the group members as I do, they’d have been at best profoundly uncomfortable at being paid; no doubt some of them would have passed the funds to other community initiatives rather than hold onto it. This type of action has, at root, a kind of internal, collective joy to it. I’m reminded of bell hooks: “One of the most vital ways we sustain ourselves is by building communities of resistance, places where we know we are not alone.” At the same time, a Freirean pedagogy of hope shows us that “to build community requires vigilant awareness of the work we must continually do to undermine all the socialization that leads us to behave in ways that perpetuate domination.” Taken together, these quotes indicate that we co-create places of belonging to nourish ourselves, while we can harness an underlying recognition of the forces we’re up against to fuel that very co-creation.

Responsiveness

The principle of responsiveness, to me, covers two main areas. First, our efforts should be based on a clear relationship to the facts on the ground of a community; they should address or respond to a preexisting drive, need, passion or surge. Second, we need to respond to change as projects progress, by adapting to unexpected circumstances or the developing wishes of those involved.

As noted, the oral history project was suggested by community members who had attended ‘Be The Media!’ in anticipation of getting to know their devices better. It was also a response to a community mapping exercise I’d undertaken, where I’d been told of the dearth of digital inclusion opportunities in the South East of Glasgow. Lastly, there is a longstanding passion in Castlemilk to stand up for itself, to challenge dominant narratives and seek social change. All of these built inertia towards a project of this sort.

In the other sense of responsiveness, we started with a blank page and discussed as a group which aspects of Castlemilk would be our focus. Over time, we gathered recordings on:

- First memories of Castlemilk

- Castlemilk Park, aka “The Woods”

- Castlemilk Stables, then and now

- Memories of, and about, Castlemilk Women

There was also one session, towards the end of our first ‘block’ of gatherings, where we decided to simply hit record and reminisce. This was a response to an oft-heard cry in our fortnightly catch-ups: “we should have recorded that!” Once more, as active participants, group members could contribute their own memories without a specific remit, allowing ideas and connections to flow in a long conversation which we then edited into a host of recollections:

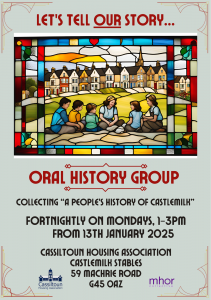

Celebration and commemoration are important, so we had planned to dovetail our website launch with the installation of a stained-glass window in Castlemilk Library. Though nobody’s fault, the window’s completion has been slightly held up, but we nonetheless wanted to share our recordings with the world. An opportunity arose to collaborate with the Stables Creative Writing Group at their summer event, so I transferred some of the memories about the Stables building onto tiny speakers, dotting them around the picturesque gardens and interweaving them with some gentle music I composed:

This echoes our intention for the Library installation, whereby QR codes are to be sprinkled through the building on a voyage of discovery. So, on a hot summer’s day, in idyllic surroundings, we wandered in and out of the reminiscences and the accompanying sounds. We felt this approach gave agency to the listeners, allowing them to choose what they heard and for how long, rather than directing them to engage in a linear sequence. It perhaps also mimics the way memory works, following chance, whim and random connections.

Diversity

In a certain sense, the oral history medium itself is an attempt to diversify the range of voices whose experience is known and cherished, and to widen the notion of history itself. We’re used to considering diversity in terms of ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and other demographic terms, but class must come into it too.

Hence oral history asks the important question “Who tells our story?” but in the act of gathering and broadcasting those stories it begins to ask a much more fundamental query: “Who are we?” Allied to this there are other factors, such as considering the social, economic or political elements that have contributed to our past and shaped our understanding of them, then and now. The act of diversifying our storytellers is a proactively political one. This touches on the notion of ‘Collective Challenge’ which I will go on to discuss below.

That said, as a group we recognised that we skewed towards older, White people who had only lived in Scotland, spoke English as a first language and had a long association with Castlemilk – all factors which limited our range as oral historians. On top of that, a thick Glasgow accent will be challenging for some listeners. We recognised the need to diversify the voices heard in our recordings, but it’s fair to say that the breadth of perspectives was still narrow. Part of that was because the network of interviewees was an organic one, as they were gathered through ‘snowballing’ via existing social ties.

We nonetheless attempted to gather younger voices such as those of Brogan:

We also tried to engage with newer Castlemilk residents who may not have been born here, such as Maja:

As a verbal medium, however, there are obvious barriers for people who may not be experienced or confident in their spoken English. That’s an issue baked into oral history. I intend to delve further into these aspects in future projects, particularly in examining how stories and experiences can be gathered that compare and contrast the lives of newer Scots and ethnic minorities alongside those who are long-term residents and/or those who are classed as White Scottish. In doing so, I hope to capitalise on an as-yet unfulfilled intention of the group: comparing their experience of moving to the area with someone retracing their steps in the modern day.

One area in which diversity excelled, though, was in the representation of women. From the outset, women formed the vast majority of people involved in the project. To anyone who has spent time being taught, tended and inspired by the women of Castlemilk, this should come as no surprise, and they were an obvious topic when we were looking for oral history subject matter.

Sustainability

The principle of sustainability is a laudable one, whereby the independence and autonomy of community members are built up so that we’re not ‘doing for’ them, we’re equipping them with skills to do themselves (or, better, doing together).

It was important, then, that I didn’t saunter into Castlemilk, recorder in hand, ready to harvest memories like the BFG storing dreams in a jar. There’s a bad faith argument that I could have done so, then created a website and claimed that site as a ‘hook’ to engage local people with the digital sphere, thus it was a digital inclusion initiative, but that’s an extractive approach that runs counter to good community work. Our group focussed on sharing the skills of audio recording so that each member could venture out, phone in hand, to gather snapshots of local history. We’d meet fortnightly to listen back to our efforts, and drop them into a WhatsApp group chat too, talking through things like sound quality, interviewing techniques and where to go next.

More broadly, our intention was to build up confidence in using smart devices generally, as I’ve already noted: key tasks such as navigating around the device and using transferable skills like saving, sharing and renaming.

In another sense though, there are risks in this mindset, because much of it is in place to make sure learners can continue to flourish after projects end. In contrast, I truly love that in Mhor, we’re not fixated on exit strategies and boundaries. Because: exit where, exactly? I live down the road from Castlemilk, and I care deeply about the people I see there. If I win the lottery tomorrow, I’m still going to be hanging about there the day after, getting the laughs about scurrilous stories from years gone by. There are massive risks in taking the Alinsky principles of ‘organising people’ and ‘working yourself out of a job’ in the wrong direction: that of always having your eyes on the door. It slides inexorably into a transactional, service-providing rubric that, frankly, jars.

Academia is as guilty as community development in this regard. There’s too much short-term, extractive work that chews people up then spits them out again, breeding apathy, disengagement and cynicism among the very ones who should be central to meaningful work. The neoliberal university is often not a structure built for long-term commitment in its research.

I get a similar unease about boundaries. While I understand the motive behind them, they’re often the right answer to the wrong question: “how can I stop caring or thinking about this when I’m not at work?” The relational, holistic, and long-term commitments we value render this question irrelevant. While I fully understand that such an approach ends up encroaching on my time off the clock, it’s infinitely better than its alternative.

At the same time, there’s a fundamental good at the core of the sustainability principle. I think, then, we need to critically ask what exactly we want to sustain, and how. I’d argue that when our focus is on nourishing social ties and the forward momentum of community power, the other stuff falls into place. When we sustain ‘being with’ – both as practitioners staying in place, and community groups staying and growing with each other – it will always naturally erode ‘doing for’. Skills are shared within and beyond groups, capacity is built, and relationships blossom.

As with so much of what we do, there’s a frustration that much of this work doesn’t show up on a stats sheet. As I’ve written elsewhere, doing one hour of digital inclusion work while spending two hours in a community space doesn’t mean my time was half-wasted; it’s absolutely core to building an understanding of the place and its people.

Holistic Approach

In lieu of repetition, I’d hope that much of the above shows how we met this principle, described as:

“ensur(ing) that digital equity projects are not just about providing tools, but also about creating supportive environments where communities can thrive digitally in a sustainable, inclusive, and meaningful way.”

My fellow group members taught me so much about being holistic, but one moment stands out. When we were jointly creating a guide to making recordings, my initial input was around the nuts and bolts of it all: try to make sure the space is quiet, avoid the risk of interruptions, check that they’ve signed the consent forms. Group members added person-centred matters I’d not even countenanced: before you start, reassure them that their stories matter, that their perspective is cherished and valued, make them feel calm, tell them they can listen back and re-record if they like. My ‘how-to’ guide had been all about the practical concerns of the recordist; their additions were about deep respect and care for people they recorded. They recognised that, even when nobody’s said outright that your voice, your perspective, your memories don’t matter, it’s implied daily. For that reason, setting is everything.

Equally, in their interactions with each other and the wider community, it was obvious that our work gathering and amplifying communal memory was “not just about providing tools, but also about creating supportive environments.” So, again, by extending the warm reach of care both within the oral history group itself, and beyond it to the community at large, we sought to embellish Castlemilk’s cohesion and build on its long history of activism and aspiration.

Collective Challenge: A Seventh Principle?

I’ll never forget a presentation I once saw from a worker at a food pantry – someone supporting a much-needed resource for their community in the grip of austerity’s vice, who, when quizzed on the projected timelines of their project, said “I hope it continues forever.” They didn’t mean that exactly, of course. They meant “for however long it’s needed.” But the language was telling: we can get so caught up in delivery, in the usefulness and strain of our efforts in the grim present, that we forget to imagine – and struggle for – a future where that need evaporates.

So, for me, all community work must include challenge, contesting the inequality at digital exclusion’s roots and directly arguing for change. It has to incorporate a bit of needle against the decision-makers and the gatekeepers, who either created or continue to uphold that inequality.

Echoing ‘Collective Care’ and the recognition of intersectionality that resides in the ‘Holistic Approach’, I’d suggest that ‘Collective Challenge’ is their partner principle. That means collectivising in two senses: collaborating with other professionals and providers to advocate with strength in depth, but more importantly to muster, motivate and maximise community members’ voices so that it’s their challenge, not ours, that makes the difference.

I was energised throughout the oral history project by the fact that the members never sought to sugar-coat the past. Pests, prejudice and precarity were referenced alongside sisterhood, smiles and solidarity.

Looping back to intersectionality, there was a clear recognition in our recordings of multiple, overlapping injustices and unfairness at those margins. Indeed, many voices also spoke of issues in the present, most notably when remembering the continuing struggles in Castlemilk for adequate food shopping. The area is a food desert, and has been badly underserved in this area:

When done well, community education in any form is more than a mere skill-share, nor is it a temporary distraction from hardship; it’s a means to an end of building community power and capacity.

It is tricky, though. Most folk will freeze up at some of the terms I’ve used here: struggle, challenge, arguing. Funders might prefer fuzzy-felt evidence of gentle joy and affirmation, while many third sector organisations often wish to project a spirit of cooperation and unity. Righteous indignation? Not so much, and solidarity without an agenda doesn’t fit in a project plan. I think, I hope, we can reclaim some of that energy, though. Feminism taught us that the personal is political. Intersectionality shows us that everything is connected. Put them together and… everything is political.

We specifically don’t want digital inclusion to burn brightly forever, because we don’t want the conditions of exclusion to smoulder. Collective challenge might be one way we can digitally include, while damping wider exclusions.

To hear and see more about the Castlemilk Oral History project, please visit their website